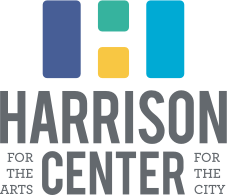

Post Traumatic Growth

“Something is wrong,” the sentence repeated over and over in Emily Wingate’s mind. This wasn’t the first time: Wingate has lived with chronic illness for years, but in 2020, following a surgery deemed successful by Wingate’s physicians, she became filled with a sense of dread. She knew something was desperately wrong; unfortunately, her instinct soon proved correct. Two weeks following the surgery, she arrived at an emergency room in St. Louis, unable to speak, her body experiencing the shock of sepsis and her heart rapidly failing.

Ablation Reverberation

Emily Wingate

Watercolor

20” x 26"

I meet Wingate for the first time in City Gallery. She speaks to a crowd of us artists at our monthly Show and Tell at the Harrison Center, and you can hear her reluctance to retell and thus relive her health experiences. She powers through, trusting the importance of processing these events with us, as they inspire her exhibit Post Traumatic Growth in the Harrison Center’s Underground Gallery.

Wildflower Garden

Emily Wingate

Watercolor

24” x 30"

“It felt like I was between two worlds,” says Wingate, as she describes being in the hospital room following the life-threatening post-surgery complications. She could feel the beginning stages of crossing over to the unknown—the real possibility of death rearing its head. This experience happened at the height of the pandemic, putting her in an impossible position: isolation. Wingate’s family had extremely limited ability to visit her inside the hospital, leaving her powerless to fully advocate for herself, forced to put her faith in a system that had repeatedly broken her trust.

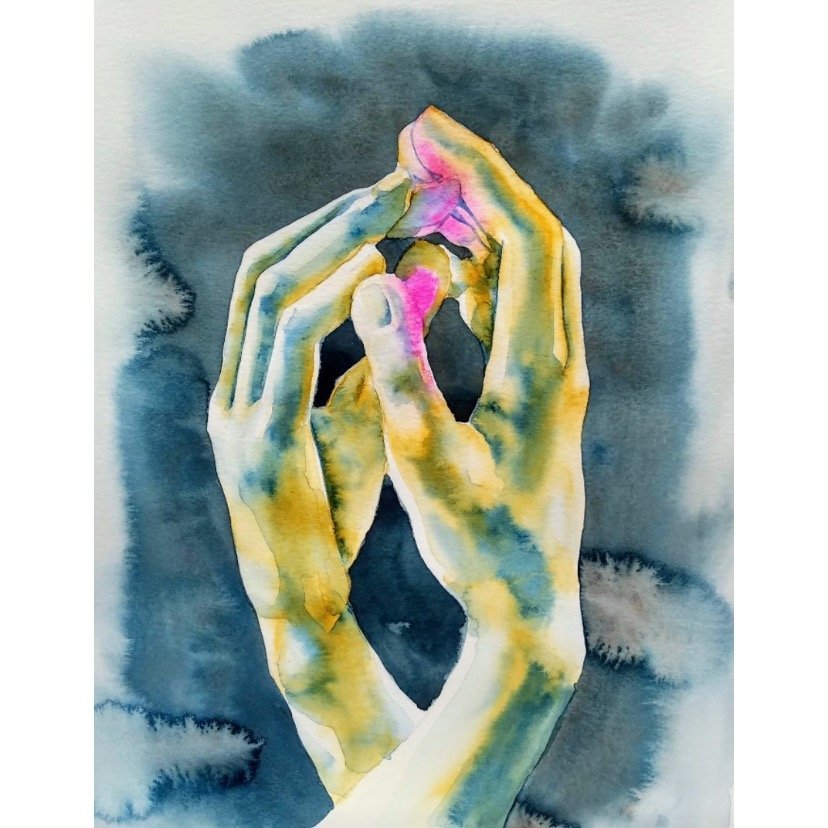

Rodin's Hands

Emily Wingate

Watercolor

12” x 14"

Soon Wingate could transfer to a new hospital and away from the difficulties of her previous care team. It was there, on a new hospital bed, in the midst of a long and difficult recovery, that she found watercolor. “I would only be able to paint for 5 minutes at a time,” she says, but what was most important to Wingate was that she found something for her hands to do. Making art was nothing new for Wingate, but these small acts of painting, experimenting for the first time with a medium like watercolor, were tiny acts of reclamation of her life: a vital form of self-care.

Magnolia V

Emily Wingate

Watercolor

9” x 12"

Wingate still lives with chronic illness, the kind of complications that make it immensely difficult to have an art practice at all. “If it were up to me, I would be painting 8 hours a day,” she laughs, and her work showcases this fact, as Wingate invested many hours into the details of these works. Wingate is a driven personality, similar to many successful artists—to put it simply, not the kind of person who wants to be taken care of. In the wake of her misfortunes, Wingate’s art practice becomes an inspiring reminder of the human need to express ourselves amidst pain, regardless of circumstance. Post Traumatic Growth is a record of a time in Wingate’s life that she never wants to return to, but by making this work, she invites us into vulnerability—a place where strange and often beautiful things can grow.

Punch

Emily Wingate

Watercolor

20” x 26"

See Post Traumatic Growth in the Underground Gallery.