Comfort Zone

In his show Comfort Zone, now on exhibit in the City Gallery, painter Willard Johnson asks us to look at Indianapolis in a different way. He wants us to remember that cities are living organisms. Not simply a conglomeration of people, streets, and buildings, cities are also home to a great deal of flora and fauna. Thinking of cities in this manner provides a glimpse into the complex relationship between the natural and man-made worlds. Willard Johnson has chosen to turn a microscope on the plant life of Indianapolis (in particular its native and invasive species) and to use plants as a metaphor for the larger story of who we are, who we were, and what we think about this place we call home.

Johnson describes the themes that inform his work as a collision of culture, religion, politics, and identity. He is no stranger to feeling out of place. Born in Seoul, South Korea, the son of missionary parents, he grew up surrounded by the vibrant cultures of South Asia and the Middle East. Johnson returned every year to Anderson, Indiana, his father’s hometown where he was reminded of his roots in middle America. Johnson’s paintings offer a lush expression of the sights, sounds, and smells of his unusual back and forth life.

Johnson earned his Master’s Degree from Cranbrook Academy of Art in 2015. Soon afterward he moved to Indianapolis to direct the Art Department of The Oaks Academy. Six years later, he still considers himself a fairly recent transplant to Indianapolis. His work teaching art to young people and his efforts to establish a home for his growing family have caused him to consider deep questions about community, rootedness, gentrification, and gardening. Johnson thinks about the terms “native” and “invasive” and how they are sometimes applied to people as well as plants. His favorite invasive species, Japanese Honeysuckle, is at the top of the Indiana Department of Natural Resources DO NOT PLANT list. Once a valued exotic ornamental it is now one of the most unwelcome plants in Indianapolis.

Japanese Honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica, was introduced to this continent in the late 19th century as an ornamental plant. A fast-growing vine-like shrub with a profusion of fragrant flowers, it has managed to escape back yards and formal gardens and wind its way into stream beds, forests, and meadows. It prefers to invade areas that have been disturbed, such as roadsides or floodplains. Once it has invaded an area, Lonicera japonica grows rapidly and outcompetes native plants for sunlight and nutrients, eventually causing the loss of native species.

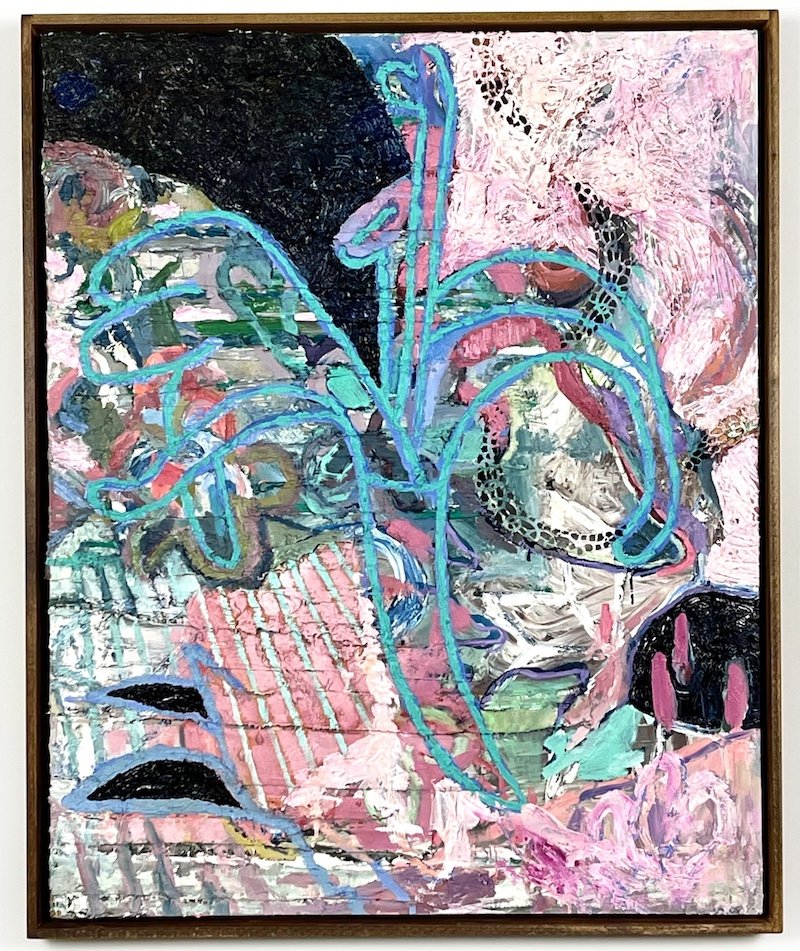

Honeysuckle blossoms appear in every painting in Comfort Zone, often serving as an illustration of a hard subject that belies the flower’s fragile beauty. Take for example the painting titled Colonial Drive. Not named after a street in Indianapolis as you might imagine, Colonial Drive refers instead to the historical compulsion of European countries to colonize other parts of the world. The canvas of this painting is made using an antique tablecloth belonging to the artist’s missionary grandmother. The silk tablecloth is torn into strips and sewn onto a canvas backing. The painted imagery is worked in multiple layers applied to the torn and sewn cloth. In some places, the artist has carved into layers of dried paint to reveal the colors beneath. Lace insets remain intact and provide a play of light and shadow on the wall behind the painting. It’s a beautiful combination of personal materials, family history, growth, loss, and a deep sense of misgiving.

Colonial Drive, Oil on canvas and silk with artist frame, 39 x 32 x 3 in

Johnson mixes his vivid oil paint with cold wax medium. Cold wax is an old technique that facilitates the creation of thick layers of separate colors. Cold wax is a combination of wax and resin that is kept soft by the addition of a solvent and can be mixed with oil paint to add bulk. As the solvent dries the mixture hardens. Johnson uses cold wax to build up layers on his surfaces like topography. He often carves through layers or creates play with shadows, texture, and surface quality. Like the builders of great cities he starts with drawings then works and reworks his compositions. Deep applications of color and texture are built upon foundations of airbrushed drawings, paper collage, and distressed fabric.

Look closely at the painting called Imperium. Among the intense color and honeysuckle blossoms, the painting is bisected by curved and angled lines. This is a map of the 465 loop as it intersects with the I-65 and I-70 split in the cities north side. Johnson was struck by the story of how the development of the highway system disproportionately affected low-income areas and communities of color, tearing apart neighborhoods and erasing long-nurtured local culture.

Imperium, Oil and airbrush on canvas with artist frame, 55 x 51 x 4 in

Intensely beautiful, Johnson's paintings arrest the viewer at first glance then reward close inspection as his imagery and methods are revealed. He demonstrates the work of a serious artist with great technical skill who approaches his subject matter with intellectual rigor. Johnson is not afraid to wrestle with difficult questions. He finds beauty in such challenges. He believes art is a way to bridge disparate subjects, often quoting one of his art heroes, the painter Gerhard Richter: “Art is the highest form of hope.” Here in Indianapolis, we need more of this.